Will Obama’s Change Come to Poor Corners of Kenya?

By By Najum Mushtaq November 11, 2008

Heavy rains in Nairobi, Kenya, since the election of Barack Obama make it almost impossible to shuffle through the mucky, narrow, and putrid streets of Kibera, one of the largest slums in Africa. But the persistent downpour last week failed to dampen the slum dwellers’ exuberance over Obama’s victory.

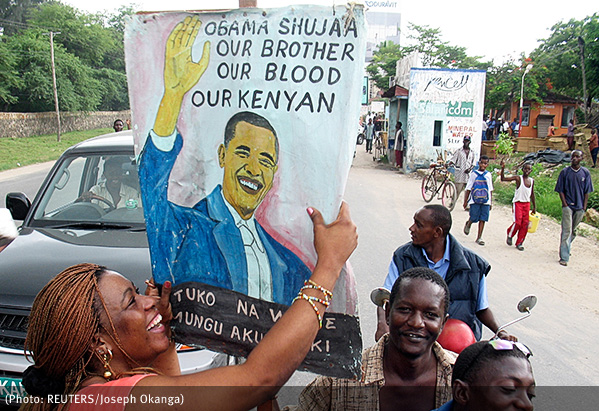

It is tempting to be cynical when a million or so inhabitants of tiny, suffocating mud and tin shacks, with no water, electricity, or toilets, forget the woes of daily existence to revel in the rare moments of hope and joy afforded them by the rise of someone regarded as one of their own to the most powerful office in the world. But of all the people outside the United States who celebrated the victory of the first man of color as U.S. president, those who came out in Kibera waving the Stars and Stripes and chanting “Yes, we can,” believe they have a more special relationship with him.

Members of the Luo tribe, from which Obama’s father came, make up the largest ethnic group in Kibera. Almost all of them have come to Nairobi from the Nyanza Province, the birthplace of the president-elect’s father. And when Obama visited the Kenyan capital in 2006, the slums of Kibera was one of the few places he visited.

“This is Illinois,” shouted a passer-by at a European camera crew filming two children playing in a mud puddle beside a dune of rubbish. “We’re going to become Illinois,” he repeated, referring to Obama’s home state.

But others are less optimistic that Obama’s change will reach so far across the globe. Peter Obiero, a schoolteacher in Nairobi, remains doubtful. Obiero recalls that at the start of the year Kibera people were equally buoyant when their member of parliament (MP) was appointed Kenya’s prime minister in a power-sharing deal to end months of post-election violence.

“Prime Minister Raila Odinga, whom the people of Kibera have elected MP for two decades, has not been able to change people’s life here. Now, the same people look to the American president for help and inspiration merely because of his roots in their tribe,” Obiero says. “In a few months, things will be back to normal.”

Not all people give in to such cynicism. “Things are different now and will never be the same for Kibera,” says Robert Kheyi, organizer of a youth group who believes Obama’s election will transform not only Kibera but also Kenya. “The impact of Obama’s victory will be profound and tangible. For one, Kenyans look at this example of peaceful elections and transition of power and begin to wonder why their own elections have to end every time in bloodshed and ethnic violence. There is a belief now that things can be different, individually and as a people.”

An immediate result, he believes, will be the return of the American tourists who deserted the country when Kenya’s election period last year turned violent. In the long run, he thinks, the country’s image, tarnished by the tribal violence, will be restored because of the international attention that the country’s association with Obama has brought.

But more significantly, a change in the image of the United States itself is shaping the public mood.

Return of the ‘Renditioned’

In a different neighborhood at the opposite end of Nairobi, reaction to Obama’s victory is more restrained and measured, though equally hopeful. This is Eastleigh, an almost exclusively Somali Muslim area and a hub of business activity. In addition to the Kenyan Somalis from the North Eastern Province, hundreds of refugees have also ended up in this unruly corner of the city. But some of its inhabitants have been paying close attention to the foreign policy of Obama for hints of what to expect.

“He didn’t once say the word ‘terror’ or ‘war on terrorism’ in his acceptance speech,” says Abdilahi Hassan, a travel agent who works in Eastleigh. “That in itself is a departure from what we have been hearing from President [George W.] Bush for the last eight years.”

No waving of American flags in this corner of Nairobi. But a sense of relief and optimism is still palpable. The main issue for these people is the U.S. “war on terror,” in which their already beleaguered country has been caught up for several years. U.S. forces and allies have been trying to hunt those responsible for the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Nairobi and Dar-es-Salam, Tanzania. In the process, the Americans have made more enemies than they have caught.

Unilateral U.S. air strikes in neighboring Somalia this year have worsened the situation as the more radical strands of the Islamic movements, claiming to be aligned with Al Qaeda, have gained in strength. These militants claimed responsibility for a series of coordinated blasts—including suicide bombings against UN targets—across northern Somalia in late October that killed more than 20.

“Despite years of civil war and statelessness, the Somali culture has never been extremist and fundamentalist in terms of religion. But the Bush policies have pushed many into the fold of Al-Shabab [the main insurgent group in Somalia]. Only a fundamental change in America’s antiterrorism policy could help to reduce the militants’ growing power,” says a bookseller in Eastliegh who did not want to be named. “Obama represents that fundamental change.”

Others, too, expect the future president’s approach to the problem of terrorism and extremism to be less militaristic. Dozens of Somali and Kenyan Muslims have been arrested and handed over by the Kenyan authorities either to the United States or transported via rendition to other countries like Ethiopia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. One man is still being held in Guantanamo Bay.

“In his campaign Obama promised to close down the Guantanamo Bay prison. Before judging him we’d like to see how and when he will deliver on this promise,” says a spokesman of the Muslim Human Rights Forum of Kenya.

Most of the renditions from Kenya—ostensibly carried out in pursuit of the war on terror—took place in January and February 2007. The Muslim Human Rights Forum says at least 20 renditions were of Kenyan citizens, most of them of Somali origin. Eight of them returned weeks ago in October, after 18 months in an Ethiopian jail. But many others languish in prisons across the world without trial or representation.

One of the Kenyans “renditioned” out of the country was Abdulmalik Muhammad, now at Guantanamo. Last month Reprieve, a British rights group that advocates freedom for Guantanamo prisoners, said that Muhammad is being held in Camp 4, which is the detention center for those considered to be “low-value” prisoners, and that the prison authorities were willing to release him.

“Declassified documents indicate that Abdulmalik was taken to the U.S. military base in Djibouti, then transferred to the Bagram Airbase in Afghanistan before his final journey to the U.S.-run Guantanamo Bay concentration camp in Cuba,” says Amin Kimathi, chairman of the Muslim Human Rights Forum, using a pejorative term for the prison.

“Apart from Abdulmalik in Guantanamo and those being detained at the Jamida prison in Ethiopia, the whereabouts of the others is still unknown,” Kimathi says. He adds, “The true indicator of what kind of change Obama will bring is whether all those Kenyan and other Muslims ‘renditioned’ on the basis of mere suspicion are able to come back to their country and whether the practice of renditions will go on even after Bush is gone.”

Najum Mushtaq is a writer based in Nairobi, Kenya, and a contributor to PRA’s Right Web (https://rightweb.irc-online.org/).