Waiting for Obama

By By Leon Hadar July 29, 2009

IT IS A FAMILIAR STORY: Israel and its global patron had a strong and unshakable relationship. Few could remember a time when the bond between the two countries was not close. And key to the partnership was the two countries’ close cooperation in containing the threat of radical Middle Eastern regimes and movements.

Following years of political turbulence and economic troubles, however, an historic election produced a major electoral realignment in the patron state. A freshly elected and very popular president took dramatic steps to transform his nation’s foreign policy, especially towards the Middle East. He withdrew military forces from an occupied Arab country and went to great lengths to improve ties with other countries in the region.

In the face of this historic change, Israel grew increasingly worried about whether the new president would continue maintaining the close, unshakeable relationship pursued by his predecessors. Its growing concerns notwithstanding, the Jewish state decided to dismiss its patron’s advice and launched a military strike against a Middle Eastern country. The patron’s new president condemned the attack and began the process of ending the diplomatic and military alliance with its Middle Eastern client. Israel thus set out in search of a new powerful patron.

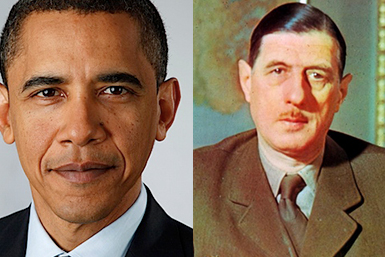

WHEN FRENCH PRESIDENT CHARLES DE GAULLE took steps to terminate the 20-year French alliance with Israel in the aftermath of its military victory in the 1967 Six-Day War, his decision sent shockwaves around the world. Israel and France had been close since the late 1940s, and their relationship turned into a full-blown strategic alliance after the popular and charismatic Egyptian army officer Gamal Abdel Nasser began providing assistance to rebels fighting French colonial rule.

In 1956, Israel joined France and Britain in an elaborate and ill-fated plan to attack Egypt and retake the Suez Canal after Nasser had nationalized it. In addition to providing Israel with sophisticated military technology, including French-made Mirage and Mystère jets, the French helped the Israelis build a nuclear reactor and a reprocessing plant. The Israel-French alliance aimed at containing the growing power of Pan Arabism was a central component in Israeli national security doctrine at the time.

But de Gaulle’s election in 1958 changed all that. Confounding many of his supporters, de Gaulle embraced a transformative foreign policy agenda that led eventually to granting independence to Algeria in 1962 and to a process of repairing relations with Egypt and the rest of the Arab World. With tension rising in the Middle East in 1967, de Gaulle pressed the Israelis not to attack Egypt and declared on June 2 an arms embargo against the country, just three days before the outbreak of the war. De Gaulle’s position in 1967 at the time of the Six Day War played a part in France’s newfound popularity in the Arab world, while Israel turned towards the United States for arms and diplomatic support.

COULD U.S. PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA play the role of an American de Gaulle? Would a decision by Israel to reject Obama’s advice against launching a military strike against Iran’s alleged nuclear sites lead to a historic reassessment in the relationship between Washington and Jerusalem?

Historian Margaret Macmillan cautions in her new book Uses and Abuses of History that while history provides useful analogies for understanding the present, they can also lead to serious errors in judgment.

So, what distinguishes the French and U.S. cases? Well, for one thing, U.S. foreign policy has traditionally been more heavily influenced by the power of public opinion, the media, and Congress than French policy, which tends to be determined by a powerful executive and elite groups. The pro-Israel orientation of the U.S. Congress has clearly played an important role in constraining any U.S. president from trying to re-orient the direction of U.S. policy in the Middle East. Hence, the expectations are that Congress will play that long-established role if Obama decides to “do a de Gaulle.”

Nevertheless, recalling the dramatic changes in French-Israeli relations in the 1960s provides us with an instructive case in point. Relationships between nation-states, and in particular between patrons and clients, are subject to change. And many Israelis, as I discovered during a recent trip to the region, are all too well aware of this.

In fact, the de Gaulle/Obama analogy was raised several times in interviews I had with Israeli officials and political analysts, reflecting the growing concern in Israel, and especially in the Likud-led government of Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu, that President Obama is intent on reshaping U.S. strategy in the Middle East. Indeed, during my visit, I was struck by the sense of inevitability shared by both Israelis and Palestinians that Washington would eventually adopt an activist role in resolving the conflict over the Holy Land.

But notwithstanding such fears on the Israeli side—and glimmers of hope among Palestinians—Obama and his aides have yet to issue any comprehensive Middle East peace plan or to take any other steps that hint of historic change, a la de Gaulle.

President Obama and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton have repeatedly asserted established U.S. positions, including the need for Israel to withdraw to the 1967 lines—with minor territorial adjustments—as part of an Arab-Israeli accord; opposition to the establishment of Jewish settlements in the occupied Arab territories; and support for the idea that the control over Jerusalem, including its religious sites, should be shared by Israelis and Palestinians.

Nevertheless, the perception in Washington and in Middle East capitals is that “something” has changed in the U.S. approach. But that “something” reflects more a change in tone and style than one of substance. There is also the sharp contrast between Obama and the George W. Bush government, which put dramatic emphasis on U.S.-Israeli ties and common interests in fighting extremism in the region. Compared to the rhetoric of Bush’s neoconservative advisors, the Obama team and its restatement of long-standing U.S. policy goals could easily appear to be ground-shaking.

THE ELECTION OF BENYAMIN NETANYAHU as prime minister of Israel also provided Obama with an opportunity to create the perception that “something” was indeed changing in the U.S. approach to the Middle East. Netanyahu has long been a favorite of U.S. neoconservatives. After their humiliating fall from power in the United States, the neocons seemed to have won a major political victory in one of the outposts of the U.S. empire with Netanyahu’s election. By endeavoring to distance himself from both Netanyahu and his neocon cheerleaders, President Obama has been able to market his message of change in the Arab World.

The political and ideological affair between Netanyahu and neoconservatives goes back to the Reagan presidency and the final years of the Cold War, when Bibi served as Israel’s representative to the United Nations and later as ambassador to Washington. The first generation of neoconservative intellectuals—including Richard Perle, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Elliott Abrams, Kenneth Adelman, and Max Kampleman—occupied top foreign-policy positions in the Reagan administration at the time. To the then-ruling Likud Party, the policies of the Republican Party seemed to offer Israel time to consolidate its hold on the West Bank and Gaza as Washington viewed the Arab-Israeli conflict through a Cold War lens, identifying Palestinian nationalism as an extension of Soviet-induced international terrorism.

As the Cold War came to end, Netanyahu returned to Israel to serve first as foreign minister and then as prime minister. He proved masterful in replacing the moribund Soviet threat with a new Middle Eastern bogeyman, persuading many beltway allies that with the Soviet Union gone, Israel could help protect U.S. interests in the Middle East against Arab nationalists (Saddam Hussein), Muslim fundamentalists (the mullahs in Iran), and the PLO, which was transformed in the Likud-neocon spin from a radical left-wing to a radical Islamic terrorist group. But George H.W. Bush and his realist foreign-policy advisers didn’t buy into this narrative and decided to confront the Likud government over the issue of the Jewish settlements in the West Bank.

After his reelection in 1996, Netanyahu paid a visit to neoconservative icon Richard Perle in Washington. According to journalist Craig Unger, the topic of their conversation was a policy paper that Perle and other analysts had written for an Israeli-American think tank, the Institute for Advanced Strategic Political Studies. Titled “A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm,” the paper proposed a radical new vision of Israeli policy. The paper proposed that by waging wars against Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, Israel—with U.S. support—could reshape the political landscape and thus ensure its security.

Netanyahu’s meeting with Obama in Washington early this year took place eight years after such ideas helped inspire one of the worst strategic fiascos in U.S. history—the 2003 invasion of Iraq. To say that Obama, unlike his predecessor, had very little interest in listening to the Israeli prime minister’s Middle East tutorials would be an understatement. Instead, Obama demanded that Netanyahu cease settlement expansion in the West Bank.

This somewhat more even-handed U.S. position has irritated Netanyahu. During his visit to Washington, Netanyahu stressed the need to deal with the potential threat of a nuclear Iran before taking steps to resolve the conflict with the Palestinians, a position that has been rejected by Obama, who has stressed that the two issues be handled congruently.

While Netanyahu has grudgingly announced that he would support the creation of a limited Palestinian state—albeit, one not acceptable to Palestinians—the Israeli government has continued to resist U.S. pressure for a complete cessation of Jewish settlement construction. Some political analysts remain skeptical about whether the Israeli leader is truly willing to embrace a two-state solution or is just trying to buy time. In any case, the conventional wisdom in Israel is that a confrontation between Obama and Netanyahu would lead to the collapse of the current Israeli government and to a new election in Israel, which could force Washington to put on hold its diplomatic push for Israeli-Palestinian peace.

The simple truth is, neither the Israelis nor the Palestinians—whose leadership is sharply divided—have leaders with sufficient charisma and authority to make the hard choices that would put the two communities on a path toward even superficial reconciliation.

CAN PRESIDENT OBAMA FILL the political vacuum in Israel and Palestine and start pressing the two sides to consider making painful compromises? Will Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and other Arab states be able to assist the Americans if and when they decide to jump into the cold water of the Middle East peace process? Will Iran and its regional allies attempt to sabotage U.S. efforts or decide to jump on the U.S.-led bandwagon? Will Obama have the political backbone to confront the powerful groups in Washington backing Netanyahu?

These are a few of the questions being asked by observers in the Middle East and elsewhere as they wait for Obama to launch his long-awaited Middle East initiative in the coming months. But another key concern is whether—Obama’s good intentions notwithstanding—the erosion in U.S. strategic and economic power might set enormous constraints on the president’s ability to transform U.S. policy in the Middle East and bring peace to the Holy Land. In the end, it may require a reckless attack by an intransigent client state on a Middle East regime to get the global patron to make the difficult steps necessary for lasting change.

Leon Hadar, a research fellow at the Cato Institute and a contributor to PRA’s Right Web (https://rightweb.irc-online.org/), is author of Sandstorm: Policy Failure in the Middle East (2006). He blogs at globalparadigms.blogspot.com.