Peace Not Near on Middle East’s “Time Horizon”

By By Leon Hadar July 29, 2008

Members of Washington’s band of foreign policy realists are high-fiving each other these days. First there was the news that the Bush administration decided to have Undersecretary of State William Burns sit in the same room in Geneva with Iranian nuclear envoy Saeed Jalili and high-ranking diplomats from five other countries and try to negotiate a deal to suspend Tehran’s plan to continue with uranium enrichment.

And then came reports that Bush agreed to set a general “time horizon” for the withdrawal of U.S. combat troops from Iraq as part of a long-term security accord that Washington is trying to negotiate with Baghdad.

If these moves seem odd, it’s probably because they came from the administration of President George W. Bush, the man who just recently compared those who would engage Iran to the “appeasers” who talked to Adolf Hitler in Munich. In the past, both Bush and the presumptive Republican presidential candidate, Sen. John McCain (R-AZ), have taken swipes at presumptive Democratic presidential candidate, Sen. Barack Obama (D-IL), for proposing that the United States and Iran hold direct negotiations—the same kind now being conducted in Geneva. And Bush and his supporters in Congress and the media have also long derided as dangerous any timetable for troop withdrawal, adamantly fighting efforts by congressional Democrats and other “defeatists” to impose what he described as “artificial” timelines for a U.S. force pullout that would supposedly play into the hands of al Qaeda and deprive America of its “victory” in Mesopotamia.

These surprising moves by Washington took place just after Israel in an uncommon step exchanged Lebanese prisoners with Hezbollah for the bodies of two Israeli soldiers. And there have been other indications that diplomacy may be replacing military force as the tool of choice in the Middle East. Israel and Syria have been holding talks under Turkish auspices that could lead to a peace agreement under which Israel will return the Golan Heights to Syria. Egypt has succeeded in brokering a temporary cease-fire between Israel and the Hamas-led government in Gaza. And Hezbollah and the pro-Western government in Beirut have agreed, thanks to Qatar’s mediation efforts, to cooperate in bringing political stability to Lebanon.

But despite all the recent progress in the Middle East, there is no real reason to think that peace is anywhere near at hand. The important common denominator of all these diplomatic openings in the Middle East has been the Bush administration’s strong resistance to them, based on the principle that the United States and its allies don’t negotiate or make deals with what Bush might describe as “Hitler equivalents”—members of the axis of evil, terrorist groups, or rogue states. Hence, talking with Iran and its partners—Hezbollah, Syria, Hamas—equals appeasement, while setting a timetable for withdrawal of U.S. troops from Iraq is tantamount to defeatism. That Israel was engaging in this kind of behavior was remarkable, but that Bush administration officials have been pursuing the same kind of policies that the president decried is nothing short of startling.

Indeed, pundits in Washington are also intrigued by the fact that these officials were pursuing diplomacy with Iran and discussing dates for troop withdrawal from Iraq in the same week that Obama, whose support for such approaches was decried by both Bush and McCain, was visiting the Middle East. Some pundits suggested that the views of the two presidential candidates on Iraq and Iran were converging in the form of a consensus on the need to start withdrawing U.S. forces from Iraq and deal diplomatically with Iran.

The signs that the realists may be winning the foreign policy debate in Washington, including in the Bush administration—where Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice pushed for talks with Iran despite opposition from Vice President Dick Cheney—came as very bad news for the neoconservatives. “Just when you think the administration is out of U-turns, they make another one,” said former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations John Bolton, who was critical of the administration’s change in policy on North Korea. Bolton adding: “This is further evidence of the administration’s complete intellectual collapse.”1

And Michael Rubin, a leading neoconservative intellectual with the American Enterprise Institute, opined in the Wall Street Journal that, “President Bush’s reversal is diplomatic malpractice on a Carter-esque level that is breathing new life into a failing regime.”2

But it’s too early for realists in Washington to celebrate victory or for neoconservatives to mourn. Realism is not necessarily on the march, and peace is hardly breaking out in the Middle East. First, much of the regional news from earlier this summer—including Israeli and Iranian war exercises, Israeli threats to strike Iranian nuclear military sites, and Tehran’s counter-threats of retaliation—indicates that the chances for a new war in the Persian Gulf remain quite high. Indeed, in an op-ed piece in the Wall Street Journal, Bolton advised policymakers in Washington to give a green light to an Israeli strike against Iran,3 while Israeli historian Benny Morris insisted in the New York Times that such an Israeli military move was all but certain.4

Although Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Adm. Mike Mullen and other members of the national security bureaucracy may be opposed to a U.S. seal of approval on an Israeli attack against Iran, it’s important to remember that President “Buscheney” retains enormous power in foreign policy decisions and setting the political agenda in Washington. It’s also unlikely that Democrats would be willing to oppose an Israeli decision to attack Iran that would be spun as a necessary defensive move against the Holocaust-denying mullahs in Tehran.

Unlike the Bush administration decision to resolve the nuclear crisis with North Korea through a broad diplomatic accord, it’s not clear that the White House is ready to take that step with Iran. The administration is still demanding that Tehran freeze its uranium enrichment program as a precondition for broader negotiations that would include, in addition to the nuclear problem, discussion over the future of Iraq and Afghanistan (where Iran maintains enormous influence) as well as the two governments’ interests in Lebanon and Israel/Palestine. When Bush and Rice decided to make a diplomatic deal with Pyongyang, they dispatched Amb. Charles Hill to hold face-to-face talks with a North Korean diplomat in Europe. A similar move toward Iran on the part of the administration would amount to the kind of “reversal” that Bolton and other hardliners and neoconservatives are decrying.

Hence, it’s quite possible that Bush and his aides have decided that they don’t have enough political support to pursue either a grand diplomatic bargain with Tehran or a military confrontation with Iran, concluding that a short-term

deal with Iran is the most cost-effective way of managing the current crisis and leaving the next U.S. president to deal with the issue in the context of his own strategy for the Middle East. Combined with the news that the United States plans to establish a diplomatic presence in Iran for the first time since the 1979-1981 U.S. Embassy hostage crisis, it suggests that there won’t be a U.S. and/or Israeli strike against Iran before the Oval Office sees a new occupant.

Or perhaps Washington’s apparent symbolic concessions toward Iran are nothing more than a diplomatic smokescreen that will allow the Bush administration to claim—before it takes military action against Iran—that it had gone out of its way to placate Iran and give it a chance to reach a peaceful agreement; Tehran, therefore, would be responsible for any ensuing conflict.

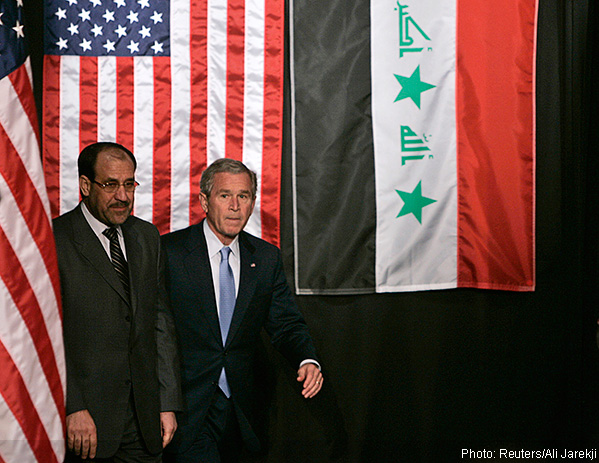

Similarly, the notion of a time horizon for withdrawing U.S. troops from Iraq is very different from drawing up a concrete timetable for pulling out U.S. forces. The idea is probably part of an effort to help Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki burnish his nationalist credentials before the upcoming Iraqi provincial elections.

Moreover, much of the diplomatic steps taken by the various Middle Eastern players in recent weeks should not be confused with a search for peace. After all, the Middle East is an area of the world where nothing is what it seems to be, where yesterday’s enemy is tomorrow’s ally, where commitments are made to be broken, and where “peace” is nothing more than a long cease-fire. It’s not a pretty picture, but it’s reality, and outsiders should not impose their wishful thinking on it.

In a way, much of what is happening in the Middle East should be regarded as efforts made by regional players to fill the diplomatic vacuum resulting from the erosion in the U.S. influence in the region, as they wait for the U.S. presidential election and the subsequent policy decisions of the new White House. It’s part of a game of wait and see—waiting, in part, to see if Bush will attack Iran—and not a sign that peace is imminent.

Leon Hadar, a research fellow at the Cato Institute and a contributor to PRA’s Right Web (rightweb.irc-online.org), is author of Sandstorm: Policy Failure in the Middle East (2006). He blogs at globalparadigms.blogspot.com.

Sources:

1. Elaine Sciolino and Steven Lee Meyers, “Policy Shift Seen in U.S. Decision on Iran Talks,” New York Times, July 17, 2008.

2. Michael Rubin, “Now Bush Is Appeasing Iran,” Wall Street Journal, July 21, 2008.

3. John R. Bolton, “Israel, Iran, and the Bomb,” Wall Street Journal, July 15, 2008.

4. Benny Morris, “Using Bombs to Stave off War,” New York Times, July 18, 2008.