“The Surge of Ideas”

By Michael Flynn June 16, 2010

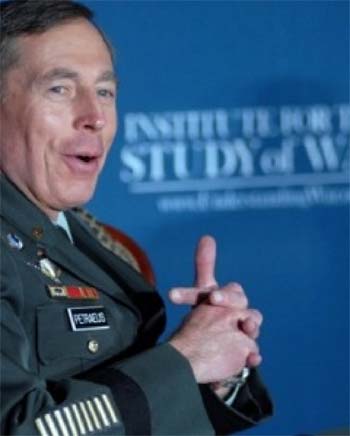

Photo: Institute for the Study of War, 2010

EARLY THIS YEAR, Gen. David Petraeus, head of U.S. Central Command, spoke at a public event in Washington, D.C., about the situation in Iraq and the priorities of the U.S. military in the greater Middle East.[1] The event was hosted by the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), a think tank led by Kimberly Kagan—spouse of the neoconservative writer Frederick Kagan—which claims to be a “non-partisan, non-profit, public policy research organization [that] advances an informed understanding of military affairs through reliable research, trusted analysis, and innovative education.”

During his presentation, Petraeus discussed everything from the challenges posed by Iran’s influence in Iraq to the non-military tactics needed to rein in Al Qaeda. Arguably the most interesting part of the presentation, however, was Petraeus’ assessment of the 2007 “surge” in Iraq. The general argued that “far more important than the surge of 30,000 additional U.S. troops was the surge of ideas that helped us to employ those troops.” Among those he lauded for waging this surge of ideas were various members of the “think tank world,” including “Kim” and “Fred,” as well as “a number of other heroes,” who Petraeus said guided a “study and analysis that did indeed have a strategic impact unlike that of any other study or analysis that I can think of.”

Petraeus was referring to “Choosing Victory: A Plan for Success in Iraq,” a study sponsored by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and led by Fred Kagan and retired Gen. Jack Keane (an ISW board member), with Kim Kagan and a host of AEI scholars (Danielle Pletka, Michael Rubin, Reuel Marc Gerecht, Thomas Donnelly, Gary Schmitt, among others) serving as advisers. The group’s report, released nearly three years to the date before Petraeus’ ISW presentation, played an instrumental role in shaping the surge and building public support for it.

Petraeus extolled his think tank “heroes” for providing “the rationale for the additional forces that were required [and] describe[ing] how they might be used in Iraq,” claiming that their work “serendipitously” made its way into “the West Wing and ultimately even into the Oval Office. … I think it played a very significant role in helping to shape the intellectual concepts and indeed, in helping to shape the ultimate policy decision that was made.” (Petraeus offered a similar account of the “surge of ideas” several months later at the American Enterprise Institute, when he was awarded AEI’s “Irving Kristol Award” in May 2010.[2])

PETRAEUS’ PRESENTATION highlighted an issue that has drawn increasing attention and criticism from commentators and foreign policy experts. In recent years there has been a tendency for like-minded think tanks and military officers to jointly pursue policy objectives, sometimes in direct conflict with the stated preferences of the president and his advisers. According to some observers, this trend raises questions about the appropriate role of both military officers, who are part of a chain of command, and think tanks, which present themselves as “non-partisan” appraisers of public policy.

The Iraq surge public relations campaign is often highlighted as a case in point. Commenting on this case, Brian Katulis, a fellow at the liberal Center for American Progress, argues that when military officers get involved in policy advocacy, it can have a “narrowing effect” on debate.

Katulis points to Petraeus’ support for the work of Michael O’Hanlon and Kenneth Pollack of the centrist Brookings Institution. In a July 2007 article for the New York Times titled “A War We Might Just Win”—a “propaganda piece,” says Katulis—the two analysts cited their military-sponsored tour in Iraq to claim that, as a result of the surge, “morale was high,” the bad guys were on the run, and while the situation remained “grave,” the military escalation merited continued congressional support.[3] Exactly the message, says Katulis, that Petraeus hoped to transmit.

Bernard Finel, a fellow at the bipartisan American Security Project in Washington, agrees, arguing that Petraeus’ decision to give a “window shield” tour to analysts like O’Hanlon was patently deliberate. During the months before his Iraq tour, O’Hanlon had helped promote the surge ideas pushed by the Kagans, coauthoring a paper with Fred Kagan and inviting him to talk at a Brookings event.

“Petraeus knew that the Bush administration’s credibility was low, that it was going to have trouble selling the surge,” said Finel in an interview, so he hand-picked a number of civilians who he knew were behind this policy and helped turn them into media “experts.” This effort sidelined critics of the surge, says Finel, who were viewed as “outsiders, people without access, and thus not to be believed.”

Just as importantly, say writers like Foreign Policy blogger Laura Rozen, the successful effort to promote the Iraq surge appears to have had an impact on Petraeus, who realized the persuasive power of getting “influence makers” to present situations on the ground “from the command’s perspective.” Wrote Rozen last year, “It’s a lesson perhaps from the Petraeus team’s famous counterinsurgency doctrine: In the campaign to win hearts and minds, don’t forget the home front.”[4]

THIS “PETRAEUS MODEL,” say Finel and Katulis, was updated late last year by Gen. Stanley McChrystal, the head of U.S. forces in Afghanistan. During much of 2009, in an effort to overcome resistance from the Barack Obama administration and push through his preferred counter-insurgency plan, McChrystal waged a public relations campaign that relied in part on a “strategic assessment” team made up of several policy wonks whose views happened to be largely in line with his own. Team members included the omnipresent Kagans, Stephen Biddle of the Council on Foreign Relations, Anthony Cordesman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Andrew Exum of the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), and Jeremy Shapiro of the Brookings Institution.

Some of these civilian experts—as well as several additional high-profile wonks like O’Hanlon, who has a knack for getting invited by the U.S. military to visit conflict zones—began appearing on major media outlets promoting ideas largely in line with General McChrystal’s, defending his decision to publicly contradict the administration in a speech, or pushing an optimistic view of the Afghan situation.[5]

Meanwhile, by late 2009, think tanks like CNAS and the Institute for the Study of War had begun holding a series of events featuring military brass discussing progress in counterinsurgency campaigns. In September 2009, for example, several CNAS scholars joined General Petraeus at a National Press Club event entitled Counterinsurgency Leadership in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Beyond, which “explored ways to improve counterinsurgency leadership, with particular attention to the leaders of American, Afghan, and Iraqi forces.”

Comments Finel of the American Security Project, “When people like McChrystal and Petraeus come out and argue for controversial polices, they turn the debate into one of patriotism and not policy. It is no longer a debate about the merits of the policy, but about how much respect you have for the military.”

IT IS A TIME-HONORED TRADITION, especially—though not exclusively—on the political right, for policy groups to pack their advisory boards with retired officers (many of whom also segue into defense industry jobs after leaving the military), who despite their apparent conflicts of interest provide an apparent sheen of seriousness and credibility. Take, for instance, the Center for Security Policy (CSP) and the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs, two neoconservative organizations whose boards are chock-a-block with defense industry executives and retired military brass.

As the New York Times reported in 2008, some of these retired officers—like Maj. Gen. Paul Vallely, a CSP advisor, and Gen. Barry McCaffery, a board member of the now-defunct Committee for the Liberation of Iraq—have developed reputations as “impartial” experts, appearing on TV news programs while surreptitiously receiving talking points from the Pentagon.[6]

There have also been cases in the past where generals shunned the chain of command to promote tactics and strategies that were opposed by the White House or Congress—for instance, Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s criticism of President Harry Truman’s limited war strategy during the Korean War and, more recently, Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Wesley Clark’s advocacy for direct U.S. military involvement in the Kosovo conflict.

However, say observers, the Afghanistan and Iraq public relations campaigns represent a troubling new trend in efforts by high-level military officials to actively court (or co-opt) organizations—both on the right (IWS and AEI) and the center (CNAS)—in an effort to shape public policy.

One source interviewed for this article, a Washington-based foreign policy writer who asked to be quoted in background so as not to jeopardize his relations in government and the non-governmental policy community, claims that there has been a “structural shift” in civilian relations to the Pentagon that to some extent was initiated by Democrats in the late 1990s. Concerned over poll numbers showing that the public did not trust Democrats on national security and hoping to cure the “allergy” many liberals had felt for the military since the Vietnam War, some elements of the Democratic Party started actively courting uniformed officers in various policy venues, including at the Council on Foreign Relations, which began a military fellows program around that time.

As a result of this effort, says the Washington-based foreign policy writer, many Democrats “became Pentagon huggers instead of Pentagon reformers” (a mantle that was left to Republicans, like the much maligned Donald Rumsfeld, to take up). These civilian-military collaborations are not all negative, he says, and they can include cooperation on a range of issues, such as how to address piracy and confront North Korea. The problem arises when the military is shown too much deference. It was out this milieu, he says, that Democratic Party-aligned hawkish think tanks like the Center for a New American Security were born.

CRITICS OF THIS TREND highlight two main problems. On the one hand, they say, military officers have an obligation not to bias the policy process. Says Finel, “In an ideal world, this is a top down situation—civilians make policy decisions, the military implements them. But the military has expertise, so they should be involved in the decision-making process. There needs to be some back and forth. … The problem is where to draw line. We reify military figures when it comes to questions of war and conflict, so they should be very careful how they impact the process.”

Other critics highlight the actions of think tanks. Says the Washington-based foreign policy expert, “The problem is that the public thinks these organizations are there to pursue the public good, to challenge public officials, not get co-opted by them.” But when you see these groups parroting military arguments to promote operations that involve a staggering amount of resources, he says, it is difficult to argue that they are fulfilling their self-defined roles, especially given the current economic crisis.

Katulis of the Center for American Progress agrees, highlighting the issue of money. When these experts are paraded on television pushing the military line based on their tours of war zones, he says, the public “doesn’t realize that these people were paid to go on these trips.” More importantly, he says, there needs to be more “transparency and accountability with respect to how these groups are financed” and what their supporters’ financial stakes are with respect to defense policies.

Adds Finel, “Sure, anyone who has a financial stake in the policies promoted by a think tank should be forced to disclose its support. But there will always be this situation of using celebrities, big names, to generate interest and, ultimately, to raise money. Everyone does it, on the left, the right, the center, thinks tanks, universities. The bigger question is how some groups and individuals game the system, generate influence through connections to the military or government, receive loads of money from corporate sponsors, and then use these connections to become enormously influential in the policy process. I mean, who elected CNAS?”

As we approach next year’s deadline to begin troop withdrawals from Afghanistan, questions about the legitimacy of joint military-wonk policy campaigns are bound to resurface. As the Inter Press Service (IPS) reported in mid-June, McChrystal and Petraeus may “be counting on pressure from the Republican Party to force President Barack Obama to reverse his present position.” According to IPS, John Nagl, head of CNAS, said as much after his organization’s recent annual conference, arguing that unless the president changes policy to give General McChrystal more time he will be vulnerable to partisan attacks during the 2012 election campaign.[7]

Michael Flynn is the director of IPS Right Web and the lead researcher of the Global Detention Project at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva.