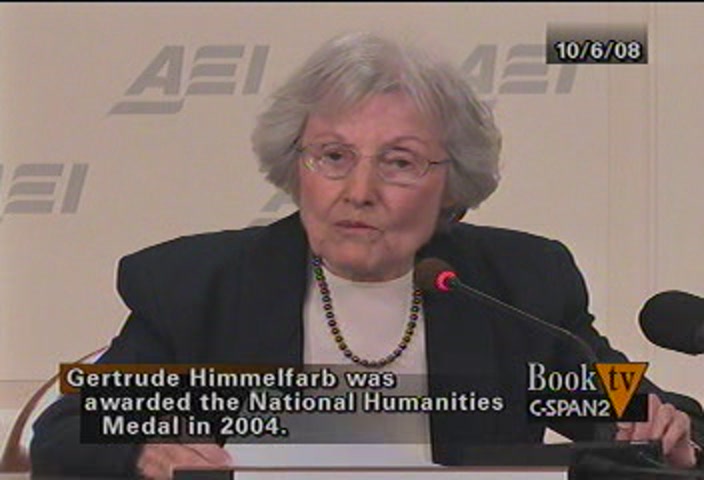

Gertrude Himmelfarb

last updated: February 19, 2014

Please note: The Militarist Monitor neither represents nor endorses any of the individuals or groups profiled on this site.

Affiliations

- American Enterprise Institute: Member of Council of Academic Advisers

- Graduate Center, CUNY: Emeritus Faculty Member

Education

- University of Chicago: Ph.D.

Gertrude Himmelfarb, the spouse of the late neoconservative trailblazer neoconservative trailblazer Irving Kristol and mother of Weekly Standard editor William Kristol, is a scholar whose work has focused on issues of virtue, morality, Victorian society, and modern values.[1]

Some writers have credited Himmelfarb with having had a decisive influence on the political evolution of her late husband. A 2014 piece in National Affairs, for example, argued that unlike other early neoconservatives—many of whom were former leftists who drifted to the right after falling out with the antiwar left—Kristol and Himmelfarb had actually begun their journey to the right much earlier under the influence of traditional conservative philosophers like Thomas Burke.[2]

The National Affairs piece argued that Himmelfarb’s influence on Kristol was fundamental in this regard. “Kristol's introduction to and extensive education in that classical liberalism came, above all, from his wife of 67 years: Gertrude Himmelfarb,” wrote Jonathan Bronitsky. “As such, Himmelfarb … should be understood to be not only an internationally esteemed historian of Victorian England but also a pivotal figure in the trajectory of neoconservatism and post-war American conservatism.” Bronitsky added, “Indisputably, Kristol and Himmelfarb's persuasion was not the same as that of many neoconservative intellectuals—especially those immersed in foreign policy. But it was essential to making possible a broader movement that indelibly shaped American conservatism and, through it, American life.”[3] (In contrast, one could point to Irving Kristol’s many publications on world affairs and U.S. foreign policy as demonstrating the critical role these issues played in his thinking and worldview.)

A prolific author on English history and what she has called “the history of ideas,” Himmelfarb has long advocated “the reintroduction of traditional values (she prefers the term ‘virtues’), such as shame, responsibility, chastity, and self-reliance, into American political life and policy-making,” according to a profile published by the Jewish Women’s Archive (JWA). In myriad writings, Himmelfarb has attributed everything from communist totalitarianism to inner-city poverty to the decline of Victorian moral sensibilities.[4]

In a 1995 Bradley Lecture at the American Enterprise Institute, Himmelfarb offered a summation of her views on the links between poverty and personal morality. “In Victorian England,” she said, “moral principles were as much a part of public discourse as of private discourse, and as much a part of social policy as of personal life. Every measure of poor relief, for example, had to justify itself by showing that it would promote the moral as well as the material well-being of the poor.” Comparing that approach to more modern sensibilities, Himmelfarb lamented, “Having made the most valiant attempt to see the problem of poverty as the product of impersonal economic and social forces, we are now discovering that the economic and social aspects are inseparable from the moral and personal ones. And having made the most determined effort to devise policies that are ‘value free,’ that do not stigmatize the recipients of relief or the ‘style of life,’ we find that these policies imperil both the moral and the material well-being of their intended beneficiaries.”[5]

Himmelfarb’s moralistic politics and historiographical methods have at times placed her at odds with academic colleagues, who prefer a more “value-neutral” approach to studying history influenced by the social sciences,[6] as well as among cultural critics who have derided her seemingly old-fashioned views.

For example, in a scathing review of Himmelfarb’s 1999 book One Nation, Two Cultures, columnist Charles Taylor wrote, “The intellect on display here is about the caliber of the village biddy who sticks her blue nose into everyone else's business, offering opinions nobody asked for about how everybody else should live. Like ‘99 Bottles of Beer,’ the tune Himmelfarb sings throughout One Nation, Two Cultures is repetitive and seemingly endless, and you always know exactly what's coming next.” Himmelfarb, Taylor wrote, “doesn't take long to get to the wicked plot: the destruction of the Victorian virtues of ‘work, thrift, temperance, fidelity, self-reliance, self-discipline, cleanliness, godliness’ (in her view, America's traditional strengths) by the Kryptonite of the '60s.”[7]

Himmelfarb’s most recent book is the 2011 The People of the Book: Philosemitism in England, From Cromwell to Churchill, an examination of historic British attitudes towards Jews. In the book, Himmelfarb posited that the lack of an explicitly “philosemitic” discourse in contemporary times reduces all discussion of Jews to a narrative of persecution and resilience, in effect objectifying them. According to a review of the book in Tablet, Himmelfarb “holds out a version of Judaism subsumed in what remains, for her, a nostalgic notion—British philosemitism as some kind of verbal antidote to Jew-hating, then and now. Would that the real-world problems of anti-Semitism and Jewish identity might be solved so easily, by invoking one magic word.”[8]

“What's often missing from this book, by and large, are actual Jews,” opined a writer for the academic blog The Little Professor. “Philosemitism, like antisemitism, consists of narratives about Jews; it does not necessarily (although it might) involve dialogues with Jews, listening to Jews, or processing that Jews and Christians might not perhaps agree on all points. I would go so far to suggest that philosemitism, like antisemitism, does not actually need Jews per se. It is here that I must dissent from Himmelfarb's definition of philosemitism as necessarily involving an act of recognition, let alone anything stronger.”[9]

Himmelfarb has written dozens of other books, including Marriage and Morals among the Victorians, De-moralization of Society: From Victorian Virtues to Modern Values, Darwin and the Darwinian Revolution, Victorian Minds, The Moral Imagination of the Late Victorians, and The Idea of Poverty: England in the Early Industrial Age.[10] In 2011, she released an updated version of her late husband’s collection of essays titled The Neoconservative Persuasion: Selected Essays, 1942-2009, which included a foreword by William Kristol.