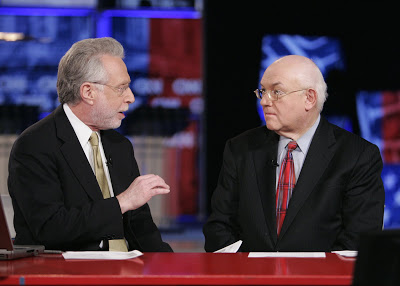

Bill Schneider

last updated: September 23, 2014

Please note: The Militarist Monitor neither represents nor endorses any of the individuals or groups profiled on this site.

Affiliations

- Third Way: Senior Fellow

- George Mason University: Professor

- CNN: Senior Political Analyst (1990-2009)

- American Enterprise Institute: Former Resident Fellow

- Atlantic Monthly: Former Contributing Editor

- National Journal: Former Contributing Editor

- Brandeis University: Visiting Professor (2002)

- Boston College: Visiting Professor of American Politics (1990-1995)

- Council on Foreign Relations: International Affairs Fellow (1979-1980)

- Hoover Institution: Senior Research Fellow (1977-1979)

- Harvard University: Associate Professor of Government (1972-1979)

Education

- Harvard University: Ph.D., Political Science

- Brandeis University: B.A.

Bill Schneider is a political analyst and commentator best known for his coverage of inside-the-Beltway politics. He gained national recognition as CNN’s senior political analyst from 1990-2009, earning such epithets as "the nation's election-meister" (from Washington Times), and "the Aristotle of American politics" (from the Boston Globe).[1] Today Schneider is a senior fellow at Third Way,[2] a Wall-Street linked Democratic think tank reminiscent of the Democratic Leadership Council, and a professor of public policy and international affairs at George Mason University.[3]

A former fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and the Hoover Institution, Schneider has experience working in the neoconservative policy community. However, unlike his more ideological peers, Schneider seldom engages in straightforward issue advocacy, preferring instead to discuss policy issues in terms of their implications for electoral politics or Beltway political discourse.

Occasionally he expresses straightforwardly interventionist views on foreign policy. “The rule in world affairs since World War II has been that if the U.S. doesn't do anything, nothing happens,” wrote Schneider in 2013, echoing arguments made by neoconservative ideologues like Robert Kagan. “If the United States had not gone to war in 1991, Kuwait would be part of Iraq. If the U.S. had not acted in Kosovo, ethnic cleansing would never have been stopped. If the U.S. had not led the invasion of Afghanistan, the Taliban would still be in power. The U.S. may have ‘led from behind’ in Libya, but U.S. enforcement of the no-fly zone was essential in ending the Qaddafi regime. It is hard to imagine a peace settlement between Israel and the Palestinians that is not guaranteed by the United States. When the U.S. failed to act in Rwanda and Sudan, the result was genocide.”[4]

Similarly, like Kagan, Schneider has argued that U.S. reluctance to invade other countries creates opportunities for U.S. rivals. “We can now see what happens when the United States retreats from global leadership,” he wrote in 2014: “ISIS and Vladimir Putin. Aggressors challenge the status quo and try to change the world map.” He added, “U.S. retrenchment is leaving a vacuum. Aggressors are moving to take advantage of it.”[5]

However, on many contemporary foreign policy questions, Schneider has been more circumspect, acknowledging both the geopolitical complexities and (more commonly) the domestic political complications surrounding questions of U.S. action without appearing to endorse any particular course.

On ISIS, for example, Schneider wrote in 2014 that “Obama presents himself as a man of reason. But you can’t reason with a savage force like Islamic State. The public wants to see some fight. … It now views Islamic State militants as bloodthirsty fanatics who must be eliminated by force.” However, remarking on the complexity of the shifting regional alliances in the Middle East, Schneider wondered, “Who are our real allies in this fight? And can we trust them to fight Islamic State militants and not each other? This is exactly the kind of political thicket Americans have no tolerance for.” He concluded, “Americans are angry at Islamic State militants, but lashing out in anger is never wise.”[6]

Before the rise of ISIS, Schneider gave some credence to arguments in support of intervening in Syria’s civil war. Citing what he characterized as “legal and humanitarian” reasons to launch an attack on the Syrian regime (in this case, its alleged use of chemical weapons), Schneider wrote that “Syria is turning into a test of U.S. credibility. If the Obama administration shows a failure of nerve with Syria, how can it be trusted to stop Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons?” He also claimed that “nothing will happen” and “the murderous bloodletting will go on” in the absence of U.S. action. However, he also praised the Obama administration for being “super-cautious” about Syria, admitted that intervention was not “necessary to protect U.S. national interests,” and ribbed the hawkish Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) as someone who “who never seems to have met a military intervention he didn't like.”[7]

Schneider has supported some of the Obama administration’s more controversial security policies, including its targeted assassination program. In a 2013 op-ed, Schneider characterized the drone war not as a war in and of itself but as part of what he called the Obama administration’s “law enforcement plus” approach to counterterrorism. In an assessment at odds with the opinion of many antiwar activists and drone war critics, Schneider concluded that insofar as it serves as an alternative to traditional boots-on-the-ground engagements, the use of drones “is true to [Obama’s] antiwar roots.”[8]

More focused on politics than policy, Schneider is often regarded as an “expert” whose credentials have been padded. “As journalist Lawrence Soley observed in 1990, think tanks have created their own 'research' journals to help mask 'the academic anemia' of their own researchers,” noted a 1997 report from the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy. “Noting that these 'journals bear names that closely resemble those of legitimate journals,' Soley states that they have produced what appears to be impressive credentials for their policy staff. At the time that Soley wrote, AEI's [Bill] Schneider, for example, had published 16 articles in the Institute's Public Opinion, but not a single article in Public Opinion Quarterly, a respected journal of social science published since 1937. Yet, Soley states, Schneider became one of the most 'sought-after' political pundits, appearing 72 times on network news programs between 1987 and 1989. He also served as a regular political commentator for National Public Radio's 'Morning Edition' during the same time period."[9]

Schneider coauthored the 1987 book The Confidence Gap: Business, Labor, and Government in the Public Mind with Seymour Martin Lipset, a well-known social scientist who in the 1970s aligned himself with the emerging neoconservative movement in the hardline wing of the Democratic Party. According to blurbs posted on the AEI website, the book purported to document the American people’s “increase in optimism during the Reagan years” after a “dramatic loss of faith in their institutions and leaders during the 1960s and 1970s.”[10]