Lewis “Scooter” Libby

last updated: May 17, 2018

Please note: The Militarist Monitor neither represents nor endorses any of the individuals or groups profiled on this site.

AFFILIATIONS

Hudson Institute: Senior Vice President

Project for the New American Century: Signatory of Statement of Principles, August 1999 Letter on Taiwan’s Defense

American Bar Association: Former Member, American Bar Association Standing Committee on Law and National Security

Rand Corporation: Former Member, Advisory Board of the Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies

GOVERNMENT

Chief of Staff to Vice President Dick Cheney: 2001-2005 (Bush Jr. Administration)

Department of Defense: Deputy Under Secretary for Policy and Principal Deputy Under Secretary for Strategy and Resources(George Bush Sr. Administration)

U.S. House of Representatives: Legal Adviser, Select Committee on U.S. National Security and Military/Commercial Concerns with the People’s Republic of China(Cox Committee)

Department of State: Director, Special Projects, Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, 1982-1985; Policy Planning Staff, Office of the Secretary, 1981

BUSINESS

Dechert, Price, & Rhoads: Former Managing Partner, Washington Office

Northrop Grumman: Former Adviser

EDUCATION

Columbia University: J.D., 1975

Yale University: B.A., magna cum laude 1972

Lewis “Scooter” Libby, Vice President Dick Cheney‘s chief of staff who was convicted in connection with the federal investigation into the PlameGate affair, is senior vice president of the neoconservative Hudson Institute.[1] Libby was a key figure in the push for the invasion of Iraq in 2003, and has long been a central figure in the neoconservative firmament.

According to his bio at the Hudson website—which fails to mention his conviction on charges of lying to government investigators—Libby “guides the Institute’s program on national security and defense issues, devoting particular attention to U.S. national security strategy, strategic planning, the future of Asia, the Middle East, and the war against Islamic radicalism.”[2]

In April 2018, President Donald Trump pardoned Libby for his conviction on outing CIA operative Valeria Plame. The move was widely interpreted as Trump’s effort to signal to associates that he would use the pardon pen to help them, and thus persuade them not to assist investigations into possible Trump-Russian collusion in the 2016 presidential election.

PlameGate

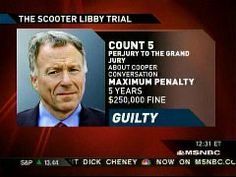

A long-standing member of the clique of hardliners and neoconservatives who pushed for the Iraq War, Libby was convicted in March 2007 on charges of lying to government investigators probing the leak of the identity of CIA agent Valerie Plame. Among the charges were two counts of perjury, one count of making false statements, and one of obstruction of justice.

Libby was fined $250,000 and sentenced to 30 months in prison.[3]President George W. Bush commuted his sentence just before he was to begin serving his time.[4]In 2013, Libby was among some 1,000 convicted felons whose voting rights were restored by Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell. In 2016, the Washington, D.C. Court of Appeals restored Libby’s ability to practice law.[5]That same year, Libby was part of the Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense, his first such public activity since his conviction.[6]Finally, on April 13, 2018, Libby was pardoned by President Donald Trump.[7]

By the time of Trump’s pardon, Libby was no longer suffering any penalties the pardon could remove. Many interpreted Trump’s decision to pardon Libby as a message to others who might be pressured to testify against him in any of the numerous investigations swirling around Trump at the time. For example, right wing blogger Jennifer Rubin—who noted that she had “long thought Scooter Libby’s conviction was unjust—wrote, “In Trump’s case, the very real possibility exists that he may use the pardon power for any number of family members and associates (e.g., [Michael] Cohen, Paul Manafort, Rick Gates, Donald Trump Jr., Jared Kushner) in an effort to prevent them from flipping and providing incriminating information about him.”[8]

Before former State Department official Richard Armitage acknowledged in September 2006 that he was the source of the leak of Valerie Plame’s identity, both Libby and the president’s Deputy Chief of Staff Karl Rove were frequently rumored to have been the initial source. As the Los Angeles Timesreported in October 2005, “Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief of staff (Libby) was so angry about the public statements of former Amb. Joseph C. Wilson IV, a Bush administration critic married to an undercover CIA officer (Plame), that he monitored all of Wilson’s television appearances and urged the White House to mount an aggressive public campaign against him, former aides say.”[9]

“While other administration officials were maintaining a careful distance from Wilson in 2004,” reported the Times, “Libby ordered up a compendium of information that could be used to rebut Wilson’s claims that the administration had ‘twisted’ intelligence to exaggerate the threat from Iraq before the U.S. invasion. Libby pressed the administration to publicly counter Wilson, sparking a debate with other White House officials who thought the tactic would call more attention to the former diplomat and his criticisms.”[10]

Those efforts by Libby began shortly after Wilson went public with his criticisms in 2003, but they continued well into 2004—after the Justice Department began investigating whether administration officials had illegally disclosed Plame’s identity.

Libby testified to a grand jury that he had met with New York Timesreporter Judith Miller on July 8, 2003 and mentioned Plame. Wilson had gone to Niger in 2002 to investigate claims that uranium yellowcake was sold to Iraq; he determined that the story was false. Miller, who in the lead-up to the Iraq invasion uncritically reported claims by administration figures that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction, spent three months in federal prison for refusing to reveal the identity of her sources about Plame’s identity. (Miller did not write an article that named Plame but was thought to have information regarding the case.) She left jail and agreed to testify after receiving a personal waiver from Libby, in which the beleaguered former insider wrote: “Out West, where you vacation, the aspen will already be turning. They turn in clusters because their roots connect them. Come back to work—and life.”[11]

On October 28, 2005, a federal grand jury charged Libby with five felonies alleging obstruction of justice, perjury to a grand jury, and making false statements to FBI agents. Soon after the announcement of the indictment, Cheney accepted Libby’s resignation and named John Hannah as his new national security adviser and David Addington as his new chief of staff.

Just before Libby was to begin serving his 30-month prison sentence, President George W. Bush commuted the sentence, arguing that it was excessive. The commutation, which left intact the federal conviction as well as a fine of more than $250,000, drew widespread criticism from across the political spectrum.

David Dow, a professor at the University of Houston Law Center, compared Bush’s decision on Libby to his failure to act while governor of Texas on cases where death row inmates requested commutation on grounds of negligent court representation, mental retardation, or having committed their crimes while minors. Wrote Dow: “I. Lewis Libby Jr. had the best lawyers money can buy. His crime cannot be attributed to youth or retardation. He has expressed no remorse whatsoever for lying to a grand jury or participating in the administration’s effort to mislead the American people about the war in Iraq. President Bush’s commutation of Mr. Libby’s sentence is certainly legal, but it just as surely offends the fundamental constitutional value of equality. Because President Bush signed a commutation, a rich and powerful man will spend not a day in prison, while 57 poor and poorly connected human beings died because Governor Bush refused to lift a pen for them.”[12]

Because of his conviction felony charges, Libby’s license to practice law was suspended in Pennsylvania and in the District of Columbia.[13]

Libby’s conviction continued to be a conservative talking point for many years. The debate was fueled by allegations that the special prosecutor who brought the case against Libby had manipulated key testimony from New York Times reporter, Judith Miller, as she detailed in a 2015 book. According to a Fox News report, “[Special Prosecutor] Fitzgerald constructed a web of lies out of Miller’s testimony in the Libby trial in order to get a conviction, by withholding exculpatory evidence from her and from Libby’s lawyers. Fitzgerald convinced (Miller) that four words in her notes from a conversation with Libby–“Wife worked at Bureau?”—had to refer to Plame working at the CIA, even though no one ever calls the CIA the Bureau. It was only years later, Miller writes, that she realized “Bureau” actually referred to the fact that Plame once had a covert job at the State Department, which is divided into bureaus—a fact that Libby never knew and had to come to Miller, she now realizes, from some other source. Fitzgerald knew the truth about Plame, as well, but withheld that vital information from her and from Libby’s lawyers.”[14]

This was an attempt to generate sympathy for Libby by proving he was not involved in leaking Plame’s identity. Outside of right wing circles, however, this alleged manipulation story did not garner much sympathy, and, since Libby was not convicted of a leak but of various incidents of perjury and obstruction—for which Miller’s new story did not exonerate him—these revelations created minimal pressure on President Barack Obama to take steps to vindicate Libby any further than his predecessor’s commutation had already done.

In a 2010 television interview, former President George W. Bush stated that his vice president, Dick Cheney, was angry at Bush’s refusal to pardon Libby as he was preparing to leave office. “Scooter is a loyal American who worked for Vice President Cheney who got caught up in this Valerie Plame case and was indicted and convicted,” Mr. Bush told NBC’s Matt Lauer. “He wanted me to pardon him. It was the last decision of the presidency, really. I chose to let the jury verdict stand after some serious deliberation, and the Vice President was angry.”[15]

At Hudson

Shortly after his resignation from the Bush administration in January 2006, Libby joined the Hudson Institute as a senior adviser, focusing on Asia and the war on terror. However, his post was short-lived. Reported Salon.com in May 2007, “Libby was indeed a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, but he apparently resigned the day after his conviction. Strangely, as far as we can tell only one other outlet, the National Journal, ever reported his resignation. He’s still hanging out with Hudson, though—two weeks after he resigned, the New York Postreported that Libby sat in the front row for a speech given by his old boss, Cheney, to Hudson Institute members.”[16]

Hudson rehired Libby at some point after 2007, and without fanfare or public announcement, he was appointed senior vice president of the institute, a position he still held as of April 2018.

The Bush Administration

Until October 2005—when he resigned after the announcement of the federal indictment against him—Libby was Cheney’s closest adviser and a key advocate of the neoconservative line in U.S. foreign affairs in the Office of the Vice President (OVP). Remarking on Libby’s influence within the OVP, Bob Woodward wrote in his 2006 book, State of Denial: “Cheney was lost without Libby, many of the vice president’s close associates felt. Libby had done so much of the preparation for the vice president’s meetings and events, and so much of the hard work. He had been almost part of Cheney’s brain.”[17]

Libby was closely associated with the clique of hardline and neoconservative advisers that was instrumental in shaping the foreign policy of the Bush administration in the wake of 9/11. However, unlike many of his fellow neocons, who tend to be prolific writers, the closest thing to a paper trail revealing Libby’s views on U.S. defense and foreign policy is the now-infamous 1992 draft Defense Planning Guidance (DPG), a controversial defense blueprint created by the few neoconservatives—including Libby—in the administration of President George H.W. Bush. The draft DPG seems to have been a major influence on the evolution of neoconservative thinking during the 1990s.

Like many other neoconservatives who populated the administration of President George W. Bush, Libby first entered government service during the Reagan years. While a student at Yale, Libby studied under Paul Wolfowitz, who became his political mentor and shepherded him into the ranks of the Republican Party’s foreign policy elite.

Also like many other neoconservatives, Libby developed strong ties with the Israeli government. In a 2015 article, Arie Genger—a businessman and political adviser, who served as the late Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s private emissary to the White House—described the very close relationship that he, as Sharon’s representative, enjoyed with Libby, as the representative of the White House.

“Scooter and I regularly exchanged views and developed a strong U.S.-Israel strategic dialogue,” Genger wrote. “He brought to these discussions tactical insights, knowledge of the region, and a nuanced grasp of American strategic interests. Intimately familiar with White House thinking, he was very inquisitive as to Arik’s (Sharon’s) real commitment to the peace process, his approach to stopping Palestinian terror, and his view of Yasir Arafat’s behavior and intentions. All this helped him assess the prime minister’s actions and test his ‘deliverables’ over time.

“Our talks soon led to a very friendly meeting with Vice-President Cheney at the White House, marking the beginning of a new period of mutual respect and trust. During his eight years as vice-president, Cheney again and again proved staunchly supportive of Israel’s security needs. In the meantime, Scooter also helped expand and improve my contacts with the National Security Council.”

Genger went on to describe the central role Libby played in internal discussion which eventually led President George W. Bush to a 2002 speech that cemented U.S. support for Israel’s policy of isolating Arafat in his Ramallah compound, where he eventually died in 2004.

Genger also describes Libby’s efforts, along with fellow neoconservative and fellow ex-convict Elliott Abrams, to press for their policies. “Throughout this often trying period, Scooter, together with Elliott Abrams, then a senior director of the NSC and special assistant to the president, sought to identify policies that would advance longer-term American interests in the region while resisting the perennial tendency of politicians and government officials to be swayed by momentary events or clamor from the media. Scooter was always there, always level-headed, always prepared to probe deeper for the facts and for the best judgment of those facts.”[18]

In 2001, Libby became chief of staff for Vice President Cheney, who also named Libby as his assistant for National Security Affairs. From 2001 to 2005, the vice president’s office became, along with that of Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, one of the key hubs of influence over foreign and military policy, sidelining the CIA and the State Department—government agencies considered inimical to the policy agenda of the military hardliners and neoconservatives.

Libby remained out of the public limelight for much of George W. Bush’s first months in office. Soon after 9/11, however, Libby’s work came under increasing scrutiny. Observers accused him of working with Cheney to bolster discredited allegations that had been used to build the case for action against Iraq, including the assertion that an agent of Saddam Hussein met with lead hijacker Mohamed Atta during the months leading up to 9/11.

In mid-2005, Libby found himself subject to widespread media attention, when his name increasingly appeared in news stories about the leak of Plame’s identity.

1992 Draft Defense Policy Guidance

In 1981 Libby joined the State Department, where he worked under his former mentor, Paul Wolfowitz on the Policy Planning Staff in the Office of the Secretary. A year later, when Wolfowitz moved over to the State Department’s Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, Libby also transferred, serving as the bureau’s director of special projects. During the George H.W. Bush administration, Libby had worked at the Pentagon under Wolfowitz and then-Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney. Libby became Vice President Cheney’s chief of staff in 2001, after the younger Bush took office.

A lawyer by training, arguably Libby’s most famous client, whom he represented from the mid-1980s to 2000, was Marc Rich, the billionaire financier convicted on racketeering and tax fraud charges who was pardoned by President Bill Clinton.

In 1992, while he was working under Cheney, Libby teamed up with Wolfowitz to write—with the assistance of Zalmay Khalilzad—the Pentagon’s new Defense Policy Guidance, or DPG. The draft version of the guidance, ordered by Cheney, laid out a military strategy for global military dominance and preventive war. A version of it was leaked to the press, and the DPG was toned down after the New York Timespublished a story about the document’s recommendations for a post-Cold War defense posture.

The draft DPG called for massive increases in defense spending, the assertion of lone superpower status, the prevention of the emergence of any regional competitors, the use of preventive—or preemptive—force, and the idea of forsaking multilateralism if it didn’t suit U.S. interests. It called for intervening in disputes throughout the globe, even when the disputes were not directly related to U.S. interests, arguing that the United States should “retain the preeminent responsibility for addressing selectively those wrongs which threaten not only our interests, but those of our allies or friends, or which could seriously disrupt international relations.” The United States must also “show the leadership necessary to establish and protect a new order that holds the promise of convincing potential competitors that they need not aspire to a greater role or pursue a more aggressive posture to protect their legitimate interests.”[19]

After 9/11, many of the ideas outlined in the draft DPG resonated with the Bush administration. When the administration released the unclassified version of President George W. Bush’s National Security Strategy, observers remarked on the many similarities between the draft guidance and the new so-called Bush Doctrine, particularly their mutual call for a preemptive defense posture.[20]

The guidance also seems to have served as a template for the founding statement of principles of the Project for the New American Century (PNAC), which was signed by a who’s who list of foreign policy hardliners and neoconservatives who joined the George W. Bush administration, including Cheney, Libby, Wolfowitz, Khalilzad, Donald Rumsfeld,Elliott Abrams, and Peter Rodman.[21] Libby, along with other PNAC principals, was part of the team that also produced the PNAC report, Rebuilding America’s Defenses: Strategy, Forces, and Resources for a New Century, which prefigured the Bush administration’s defense policy and budget.

SOURCES

[1]Hudson Institute, “Lewis Libby,” http://www.hudson.org/learn/index.cfm?fuseaction=staff_bio&eid=LewisLibby.

[2]Hudson Institute, “Lewis Libby,” http://www.hudson.org/learn/index.cfm?fuseaction=staff_bio&eid=LewisLibby.

[3]Carol Leonnig and Amy Goldstein, “Libby Given 21/2-Year Prison Term,” Washington Post, June 6, 2007, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/06/05/AR2007060500150.html

[4]Amy Goldstein, “Bush Commutes Libby’s Prison Sentence,” Washington Post, July 3, 2007, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/07/02/AR2007070200825.html

[5]Ann E. Marimow, “Scooter Libby cleared to practice law again,” Washington Post, November 8, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/public-safety/scooter-libby-cleared-to-practice-law-again/2016/11/08/db41a556-a5d6-11e6-ba59-a7d93165c6d4_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.c1ca94b3e4e8

[6]Richard Sisk, “Scooter Libby Resurfaces on Biodefense Panel,” Military.com, February 3, 2016, https://www.military.com/daily-news/2016/02/03/scooter-libby-resurfaces-on-biodefense-panel.html

[7]Kevin Liptak, “Trump pardons ex-Cheney aide Scooter Libby,” CNN, April 13, 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2018/04/13/politics/donald-trump-pardons-scooter-libby/index.html

[8]Jennifer Rubin, “Is Trump’s pardon of Scooter Libby a warm-up for a constitutional crisis?” Washington Post, April 16, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/right-turn/wp/2018/04/16/is-trumps-pardon-of-scooter-libby-a-warm-up-for-a-constitutional-crisis/?utm_term=.6f576f7ff7f9

[9]Peter Wallsten and Tom Hamburger, “Bush Critic Became Target of Libby, Former Aides Say,” Los Angelese Times, October 21, 2005, http://articles.latimes.com/2005/oct/21/nation/na-libby21.

[10]Peter Wallsten and Tom Hamburger, “Bush Critic Became Target of Libby, Former Aides Say,” Los Angelese Times, October 21, 2005, http://articles.latimes.com/2005/oct/21/nation/na-libby21.

[11]Quoted in Daniel Engber, “Do Aspens Turn in Clusters?” Slate.com, October 17, 2005, http://www.slate.com/id/2128205.

[12]David Dow, “Independence Day: The Drama of Bush and Libby,” New York Times, July 4, 2007.

[13]Carter, Ledyard, and Milburn LLP, “Paths Back to Professional Work after a Felony Conviction,” November 15, 2007, http://www.clm.com/publication.cfm/ID/155.

[14]Arthur Herman, “How the obsessive, dishonest prosecution of Scooter Libby almost cost us Iraq,” Fox News, April 8, 2015, http://www.foxnews.com/opinion/2015/04/08/how-obsessive-dishonest-prosecution-scooter-libby-almost-cost-us-iraq.html

[15]Lucy Madison, “George W. Bush: Dick Cheney Was Angry I Didn’t Pardon Scooter Libby,” CBS News, November 8, 2010, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/george-w-bush-dick-cheney-was-angry-i-didnt-pardon-scooter-libby/

[16]Alex Koppelman, “On behalf of I. Lewis Libby,” Salon.com, May 31, 2007, http://www.salon.com/news/politics/war_room/2007/05/31/libby_sentencing/index.html.

[17]Bob Woodward, State of Denial: Bush at War, Part III (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006).

[18]Arie Genger, “Why Ariel Sharon Thanked Scooter Libby,” Mosaic, May 6, 2015, https://mosaicmagazine.com/observation/2015/05/why-ariel-sharon-thanked-scooter-libby/

[19]Excerpts of the 1992 Draft Defense Policy Guidance (PBS.org), http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/iraq/etc/wolf.html.

[20]Chris Dolan and David Cohen, “The War about the War: Iraq and the Politics of National Security Advising in the G.W. Bush Administration’s First Term,” Politics & Policy, Volume 34, No. 1, March 2006.

[21]Statement of Principles, Project for the New American Century, June 3, 1997, http://www.newamericancentury.org/statementofprinciples.htm.